Peace: political participation, peace and access to justice

PEACE

Education can encourage constructive political participation: In 106 countries, people with higher levels of education were more likely to engage in non-violent protests. In 102 countries, adults with a tertiary education were 60% more likely to request information from the government than those with a primary education or less.

Education needs to be better recognized in peace agreements: It was mentioned in only two-thirds of such agreements between 1989 and 2005.

Only the right type of education works: In Rwanda, curricular content exacerbated Hutu-Tutsi divisions.

Conflict is destroying education: Of those out of school, 35% of children of primary school age, 25% of adolescents of lower secondary age and 18% of youth of upper secondary age live in conflict-affected areas.

Education helps people get access to justice systems: In 2011, in Macedonia, 32% of those with primary education understood the judicial system, compared with 77% with higher education.

Persistent violence and armed conflict undermine personal security and well-being. Preventing violence and achieving sustainable peace require democratic and representative institutions and well-functioning justice systems. Education is a key element in political participation, inclusion, advocacy and democracy. While education can contribute to conflict, it can also reduce or eliminate it. Education can play a vital role in peacebuilding and help address the alarming consequences of its neglect. Education initiatives, in particular driven by civil society organizations, can help marginalized populations gain access to justice.

EDUCATION AND LITERACY MAKE POLITICS MORE PARTICIPATORY

Education increases knowledge about key political leaders and the workings of political systems. Individuals need information and skills to register to vote, understand the stakes and take an interest in election results. In western Kenya, a scholarship programme targeting girls from politically marginalized ethnic groups led to increased secondary school participation and boosted their political knowledge. In Pakistan, a voter-awareness campaign before the 2008 elections increased women’s likelihood of voting by 12 percentage points. In Nigeria, an anti-violence campaign before the 2007 elections reduced intimidation and led to 10% higher voter turnout.

Better education can also help people be more critically minded and politically engaged, and can increase representation by marginalized groups. Students are more likely to engage in politics with well-designed civics education and an open learning environment that supports discussion of controversial topics and allows students to hear and express differing opinions. A study of 35 countries showed that openness in classroom discussion led to an increase in the intention to participate in politics. In Israel and Italy, an open, participatory classroom climate has been shown to help students become more civically and politically involved.

Better education and women’s involvement in national and local decision-making bodies are closely linked. Greater representation of women in politics and public office can reduce gender disparity in education by providing positive role models for women and increasing their educational aspirations. Across India’s 16 biggest states, increasing the number of women involved in district politics by 10% would lead to a nearly 6% rise in primary school completion, with a larger impact on girls’ education.

Higher literacy levels accounted for half the regime transitions towards democracy between 1870 and 2000

Education makes it more likely that discontented citizens will channel their concerns through non-violent civil movements such as protests, boycotts, strikes, rallies, political demonstrations, social non-cooperation and resistance. Across 106 countries over 55 years, ethnic groups with more education were more likely to engage in non-violent protests.

Broad and equitable access to good quality education helps sustain democratic practices and institutions. Higher literacy levels accounted for half the regime transitions towards democracy between 1870 and 2000.

EDUCATION AND CONFLICT: A COMPLEX RELATIONSHIP

The poverty, unemployment and hopelessness resulting from the lack of a good education can act as recruiting agents for armed militia. In Sierra Leone, young people with no education were nine times as likely to join rebel groups as those with at least secondary education. Inequality in education exacerbates the issue. Data from 100 countries over 50 years found that those with wider education gaps were more likely to be in conflict. Yet more education is not a panacea: When education levels rise but labour markets are stagnant, frustration can boil over.

Schools that inculcate prejudice, intolerance and historical distortions can become breeding grounds for violence. In many countries, curricula and learning materials have been shown to reinforce stereotypes and exacerbate political and social grievances. In Rwanda, a review of education policies and programmes over 1962–1994 found that the content contributed to categorizing and stigmatizing Hutu and Tutsi into exclusive groups. Language in education can also be a source of wider grievances.

Data from 100 countries over 50 years found that those with wider education gaps were more likely to be in conflict

Armed conflict is one of the greatest obstacles to progress in education. In conflict affected countries, 21.5 million children of primary school age (35% of the total) and almost 15 million adolescents of lower secondary age (25%) are out of school. In the Syrian Arab Republic, over half a million children

were out of primary school in 2013. Schools are often used for military purposes. Teachers are at risk: In Colombia, 140 teachers were killed between 2009 and 2013. Widespread forced recruitment of children into armed groups persists.

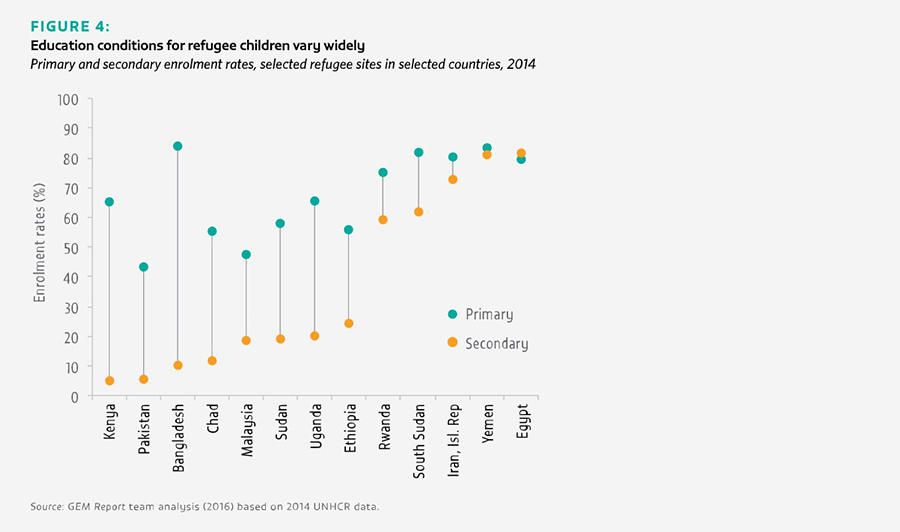

Refugees present a huge challenge for education systems. Refugee children and adolescents are five times likelier to be out of school than their non-refugee peers. In some refugee settings, pupil/teacher ratios are as high as 70:1 and many teachers are unqualified.

Education can help address differences between ethnic and religious groups. But where schools maintain the status quo through curricula or school segregation, they can ingrain discriminatory attitudes. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, schools have been segregated along ethnic and linguistic lines since the end of the war in 1996. Curricular content can help or harm intergroup relations after conflict. The success of any curricular reform

depends on the availability of motivated, engaged and trained teachers.

Well-designed formal and non-formal peace education can reduce student aggression, bullying and participation in violent conflict. Education needs to be integrated in international peacebuilding agendas, but security issues tend to be prioritized instead. Of the 37 publicly available full peace agreements signed between 1989 and 2005, 11 do not mention education at all.

EDUCATION CAN BE CRUCIAL IN BUILDING A FUNCTIONING JUSTICE SYSTEM

A functioning justice system is critical for sustaining peaceful societies. However, many citizens lack the skills to gain access to complex justice systems. In 2011, according to court user survey results in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, only 32% of individuals with primary education were well or partially informed about the judicial system and its reforms, compared with 77% of those with higher education. Community-based education programmes can help increase understanding of legal rights, particularly for the marginalized.

Building the capacity of judicial and law enforcement officers is critical. Insufficient training and capacity-building can hold back justice and result in delays, flawed or insufficient evidence-gathering, lack of enforcement, and abuse. In Haiti, the national police went from being the least to the most trusted public institution over five years through a seven-month UN recruit training programme.