People: inclusive social development

PEOPLE

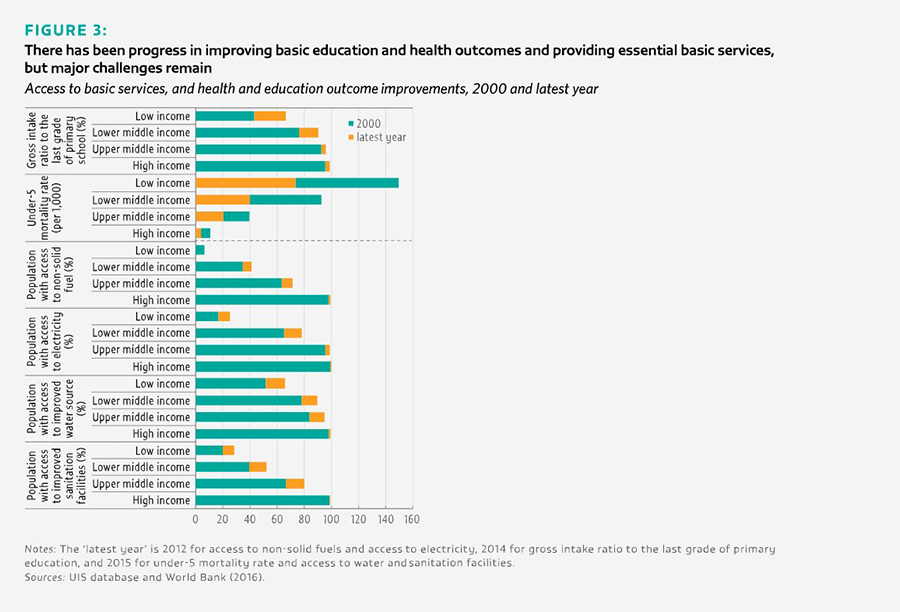

Millions, particularly the marginalized, lack access to basic services: In 2012, in low income countries, only 28% had access to sanitation facilities and 25% to electricity; 67% made it to the last grade of primary education.

Gender equality is a long way off: Only 19% of heads of state or government are women. Women in many countries do at least twice as much unpaid work as men.

Education improves health and reduces fertility rates: Educating mothers increased reliance on exclusive breastfeeding by 90% for the first six months. Four years more in school in Nigeria reduced fertility rates by one birth per young girl.

Health and nutrition improve education: Female literacy rates were 5% higher for those with better access to water in India. In Kenya, girls who received deworming treatment were 25% more likely to pass the primary school exam.

Social development leads to improvements in human well-being and equality and is compatible with democracy and justice. Education is a powerful enabler, and a key aspect, of social development. It is central to ensuring people can live healthy lives and improve their children’s lives. It can enhance gender equality by empowering vulnerable populations, a majority of whom are girls and women.

Education is interlinked with other sectors, just as health, nutrition, water and energy sources are central to education. Children’s health determines their ability to learn, health infrastructure can be used to deliver education, and healthy teachers are indispensable to education sector functioning.

Ultimately, a holistic approach to human development is needed to address multidimensional poverty challenges.

INCLUSIVE SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT IS CRITICAL TO SUSTAINABLE FUTURES FOR ALL

Inclusive social development requires universal provision of critical services such as education, health, water, sanitation, energy, housing and transport, which is far from the case at present. Despite progress, substantive gender equality also remains elusive in most countries – for example, women do at least twice as

much unpaid work as men, and often work in the informal sector.

Women do at least twice as much unpaid work as men

Inclusive social development demands addressing entrenched marginalization and discrimination against women, people with disabilities, indigenous populations, ethnic and linguistic minorities, refugees and displaced populations, among other vulnerable groups. To change discriminatory norms and empower women and men, education and the knowledge it conveys can be improved to influence values and attitudes.

Many groups are marginalized in terms of education access and quality, including racial, ethnic and linguistic minorities, people with disabilities, pastoralists, slum dwellers, children with HIV, ‘unregistered’ children and orphans. Differences in income, location, ethnicity and gender account for patterns of educational marginalization within countries. Poverty is by far the greatest barrier to education. Among 20- to 24-year-olds in 101 low and middle income countries, the poorest have on average 5 years fewer schooling than the richest; the gap is 2.6 years between urban and rural dwellers, and 1.1 year between women and men.

These factors often overlap. For instance, females from poor, ethnically or spatially marginalized backgrounds often fare substantially worse than their male counterparts. In a majority of countries, less than half of poor rural females have basic literacy skills. In countries such as Afghanistan, Benin, Chad, Ethiopia, Guinea, Pakistan and South Sudan, where disparities are extreme, the poorest young women have attained less than a single year of schooling.

EDUCATION IMPROVES SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT OUTCOMES

Education can improve social development outcomes across a range of areas, notably health and women’s status.

It provides specific skills and knowledge on health and nutrition, changing behaviour in ways that improve medical conditions. In India, Indonesia, Paraguay and the United Republic of Tanzania, poor, less educated patients had access to less competent doctors.

School-based interventions, such as meals and health campaigns, can have an immediate impact on health. Conversely, meals in schools may increase attendance. In northern rural Burkina Faso, daily school lunches and a take-home ration increased female enrolment by five to six percentage points after one year.

School-based interventions can provide information on health and lead to behavioural change. Many water, sanitation and hygiene interventions in schools improve health and economic and gender equity. In Finland, school meals are viewed as an investment in learning and a way to teach long-lasting eating habits and promote awareness of food choices.

Four extra years in school in Nigeria was estimated to reduce fertility rates by one birth per girl

Individuals and societies benefit when girls and women receive better quality education. Education broadens women’s employment opportunities. Literacy skills help women gain access to information about social and legal rights and welfare services. Education can increase women’s political engagement by imparting skills that enable them to participate in democratic processes. Low levels of education are a significant risk factor in intimate partner violence.

More educated mothers are better able to feed their children well and keep them in good health. Mothers’ education also has powerful intergenerational effects, changing family preferences and social norms. Four extra years in school in Nigeria was estimated to reduce fertility rates by one birth per girl. Short-term education supporting mothers of young children can have a significant impact on health and nutrition. Targeted nonformal education may be effective in helping women plan childbirth.

Education can reduce maternal mortality. Increasing female education from zero to 1 year would prevent 174 maternal deaths per 100,000 births.

SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT INFLUENCES EDUCATION

Just as education has positive effects on social development, social development affects education, both positively and – where not inclusive – negatively. Health and nutrition form a foundation for education systems: They condition children’s ability to attend school and learn, and their families’ ability to support

them. In Kenya, girls who received deworming treatment were 25% more likely to pass the national primary school exit exam. Living conditions in early childhood set the stage for learning. Access to quality health care for teachers can reduce teacher absenteeism and attrition.

Access to water, sanitation, hygiene and energy has a positive influence on education. In Ghana, halving water fetching time increased school attendance among girls, especially in rural areas. In rural Peru, as the number of households with access to electricity increased from 7.7% in 1993 to 70% in 2013, children’s studying time rose by 93 minutes a day.

INTEGRATED SOCIAL AND EDUCATION INTERVENTIONS ARE NEEDED

Progress in gender parity in education has not systematically translated to gender equality. For example, in Asian countries such as Japan and the Republic of Korea, while women’s education has risen, female labour force participation remains limited despite demand for educated labour due to an ageing workforce. Similarly, sustained health-related behaviour change is not possible with education interventions alone.

These patterns underscore the need for broader interventions and policies that integrate education with actions such as legislative change or workforce policies. Social protection programmes that seek to reduce risk and vulnerability – such as pensions, cash transfers and microfinance – can have outcomes in multiple areas, from lessening poverty to improving access to education. For instance, family-friendly policies and flexible work arrangements can encourage continued female labour force participation.

Addressing deep-set gender bias through programmes that bring men and women together can be effective. In Brazil, Program H includes group education sessions, youth-led campaigns and activism to transform gender stereotypes among young men; it has been adopted in over 20 countries.