Work

ACHIEVING GENDER EQUALITY REQUIRES MAJOR TRANSFORMATION

Ensuring gender equality in health, political and economic leadership and employment, not just gender parity in education, underpins the sustainable development agenda. This section analyses issues related to gender inequality and equality by focusing on three themes – work and economic growth; leadership and participation; and relationships and wellbeing– all of which are linked with education, gender and sustainable development. The section highlights selected gender-related challenges, practices and trends involving education, along with other dimensions of sustainable development that need to be addressed to enable progress in gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls.

Education, Gender and Work

Good quality education and lifelong learning can enable women and men to participate equally in decent work, promoting economic growth, poverty reduction and well-being for all.

Sustainable development implies inclusive economic growth focused on human welfare and planetary survival. To achieve social cohesion and transformational change, prosperity must be conceived in ways that leave no one behind.

ADDRESSING GENDER INEQUALITY IN THE LABOUR MARKET

Widespread inequality, including endemic gender discrimination in the labour market, significantly affects women’s and men’s participation in formal and informal employment. On average, women fare worse than men when employment opportunities are evaluated by indicators used as proxies of decent work, such as the extent to which people have stable, formal employment with security in the workplace and social protection for families, or employment providing a wage above poverty level (ILO, 2007).

In many contexts, women disproportionately work in the informal economy – which is partly outside government regulation and taxation – in countries with high levels of informality (Figure 11), and in agriculture, without owning land and assets. Women also tend to be over-represented in vulnerable employment, working on their own or with one or more partners, or as unpaid family workers. Eliminating women’s socio-economic disadvantage is necessary for achieving substantive gender equality (UN Women, 2015c).

Gender disparity in informal and vulnerable employment often varies by country and region. Analysis for the 2016 GEM Report using the World Bank Skills Toward Employment and Productivity (STEP) data on the urban populations of 12 low and middle income countries found informality to be highest among men in Central Asian and Eastern European countries, but higher among women in Latin American and sub-Saharan African countries (Chua, 2016). Even wage work may not be enough to escape poverty. Across all 12 countries, women are more likely than men to be classified as working and poor (Chua, 2016). On average, working poverty among women is double that of men. Large disparity is also found in many OECD countries, including Austria, Finland, the Republic of Korea and Switzerland, where twice as many women as men work on low pay (OECD, 2016a).

Women fare worse than men when proxies of decent work are used to make comparisons

Education can provide skills for work …

Education has a well-established effect on earnings. The rates of return to education are highest in poorer regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa, reflecting scarcity of skilled workers (Montenegro and Patrinos, 2014). Formal education of good quality equips individuals with skills and knowledge to become more productive. Completion of schooling can also act as a signal of ability to employers, providing access to decent work opportunities, irrespective of actual knowledge and skills acquired during study. In the OECD, differences in cognitive skills accounted for 23% of the gender gap in wages in 2012(OECD,2015b).

Marked differences in labour market outcomes, such as employment rates and wages, tend to decrease among more highly and similarly educated women and men (Ñopo et al., 2012; UNESCO, 2014). But differences in educational attainment account for a significant proportion of employment disparity in some STEP countries where women are most educationally disadvantaged. Analysis suggests that equalizing educational attainment would reduce disparity in informal employment by 50% in Ghana and 35% in Kenya, with working poverty dropping by 14% and 7%, respectively (Chua, 2016).

… but the links between girls’ education and labour force participation are not straightforward

Achieving gender parity in education, while important, does not necessarily translate into gender equality in economic activity and employment opportunities. Countries that have seen rapid growth in education attainment among girls have not seen commensurate increases in decent work (Figure 12). In Sri Lanka, significant improvement in female enrolment and completion has not translated into workforce advantages; instead, female labour force participation has been stagnant or decreasing(Gunewardena, 2015). In Latin America and the Caribbean, improvements in girls’ education at all levels have been a significant factor in women’s rising labour market involvement, yet in the Middle East and North Africa, only tertiary education has had a significant effect on increasing employment (ILO, 2012). Similarly, high income Asian countries such as Japan and the Republic of Korea have limited female labour force participation despite high levels of education (Kinoshita and Guo, 2015). Analysis of STEP data showed that the gender gap in educational attainment did not explain gender differences in informal employment among the sampled countries; other factors, including discrimination and gendered cultural norms, were likely to contribute to women not having equitable access to stable, decent work (Chua, 2016). In Ghana, women’s education and labour force participation increased from the mid-1990s, yet their wage employment stagnated and unemployment rose, along with informal economic activity and self-employment. More years of education did increase chances of wage employment (Sackey,2005). Research suggests that empowering women requires matching education reforms with better access to public-sector jobs or laws ensuring that private employers provide decent work (Darkwah, 2010).

Non-formal education can help provide skills for work

Non-formal learning opportunities tailored to local needs – community-based ‘second-chance’ programmes, microfinance initiatives or vocational training, and informal learning – can provide essential skills to young adults who have been failed by low quality education systems. Women and girls, in particular, can benefit from such programmes, as women account for almost twothirds of the 758 million adults globally who lack literacy skills (UNESCO, 2016d).

In Egypt, the Females for Families programme identified inadequate health and education services, illiteracy, early marriage and poor attitudes towards girls as key challenges for local communities. Community-based training was provided for girls in literacy, health and other skills. Girls then established home literacy classes,which addressed daily problems; gave out health,hygiene and family planning information; trained people in cooking, crafts or agriculture; encouraged children to return to school; and helped community and family members secure small loans and obtain identity and election cards. They became community leaders (UNESCO, 2016c).

Empowering women requires matching education reforms with better access to publicsector jobs or laws ensuring that private employers provide decent work

In many countries, especially in poorer countries in Asia and Africa, women are a large share of farmers and agricultural workers but are less likely than men to have access to agricultural extension and advisory services (FAO, 2014). In India, over 250,000 women farmers have been supported since the 2010 launch of the government project Mahila Kisan Sashaktikaran Pariyojana (Strengthening Women Farmers), which trains community resource people to enable, support and build capacity among women for sustainable agricultural production (Centre for Environmental Education India, 2016).

ADDRESSING SOCIOCULTURAL GENDER NORMS FOR INCLUSIVE ECONOMIC PROSPERITY

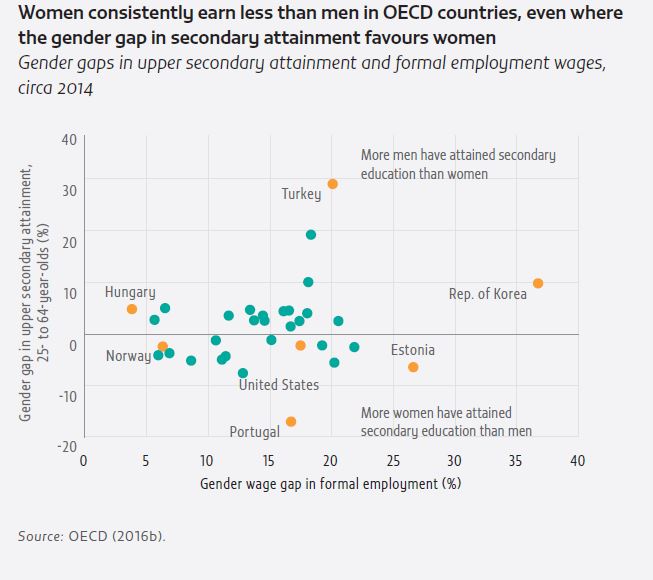

The ways women and men participate differently in labour markets are determined not only by educational attainment but also by other influences that affect wage levels: available job types, access to resources, and bias in markets and institutions (ILO, 2016c; World Bank, 2011). Cultural norms and discrimination limit the extent to which well-qualified women gain access to better-paid occupations and rise within work hierarchies (World Bank, 2011). Within institutions, women can find it difficult to reach senior positions, hitting a ‘glass ceiling’. Relatively few women occupy leadership positions in key economic institutions. Significant pay gaps exist between women and men doing the same job in virtually all occupations (UN Women, 2015c). While women’s secondary attainment is now higher than men’s in many OECD countries, the gender pay gap favouring men remains substantial in many member countries (Figure 13).

Education can address gender bias in occupations

Analysis of occupational and educational trends shows that women and men continue to be concentrated in different labour market sectors, such as teaching (women) and information and communication technology (ICT) (men), often with different levels of status, remuneration and security (Figure 14). According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), such occupational segregation was decreasing until the 1990s, but has since risen (ILO, 2012, 2016c). This has mainly favoured men overall in terms of pay and status (ILO, 2016c), but not all men benefit.

Particularly in developing countries where occupational safety and health standards are weaker, men are more likely than women to work in hazardous occupations, including mining and construction, where injury, work related diseases and death rates are higher than other occupations (ILO, 2009).

Occupational segregation is linked to basic education experience and subject choice at higher levels of education, which are still marked by strong gender differences. In OECD countries, only 14% of young women entering higher education for the first time in 2012 chose science related fields of study,compared with 39% of young men. Girls are much less likely to consider a career in computer science, physics or engineering – key sectors in the knowledge economy (OECD, 2015a). In the United States in 1983/84,37% of computer science bachelor’s degree graduates were women, but by 2010/11 the share had fallen to 18% (US Department of Education, 2012). In countries with data on tertiary education subject choice, the average female share of education majors was over 68%, compared with 25% in engineering, manufacturing and construction (Figure 15).

This disparity limits women’s access to key professions. It also reduces the potential pool of talent for developing sustainable green innovation (UNESCO, 2016d). Stereotyped gender roles and expectations in school and at home partly explain educational and occupational segregation. Socialization processes, including poor career counselling, lack of role models, negative familial attitudes, perceived inability in mathematics and fear of being in the minority, may influence girls’ willingness to choose specific disciplines. Teachers can affect subject choice. Lessons can allow students to critically reflect on gendered norms. This in turn can help break occupational stereotypes and help address gendered segregation. Targeted initiatives can encourage more gender-equitable selection of school subjects such as science, mathematics and computing (Box 2).

Box 2

Initiatives for girls and women in STEM and STEAM

In recent decades, national initiatives have encouraged girls and women to take up science, technology, engineering and mathematics, known as the STEM subjects.

Launched in 1984, the Women in Science and Engineering campaign in the United Kingdom promotes engineering apprenticeship programmes, scholarships for women studying engineering, workshops on careers in construction and engineering, resources for teachers of STEM subjects in schools, and regional networking opportunities to help develop links between schools, universities and industry. The TechWomen programme uses mentorship, knowledge exchange and networking to connect and support women in STEM from Africa,Central Asia and the Middle East. Participants engage in project-based mentorships at leading technology companies in the United States and are encouraged to inspire other girls and women in their communities to follow their ambitions. Since 2011, 333 women from 21 countries, including Algeria, Cameroon, Lebanon, Kazakhstan, Kenya and Zimbabwe, have participated.

In June 2016, the U.S. Mission to UNESCO and partners launched a comprehensive approach to ‘STEAM’ education, incorporating ‘arts’ (and design) in the acronym to encourage innovative cross-disciplinary skills and initiatives.

Sources: TechWomen (2016); WISE (2016); US National Commission for UNESCO (2016).

Policies can support women’s employment

While skills and education can help reduce wage differences between women and men, additional policy interventions are required, particularly for those working in low paying, less secure jobs, often in the informal sector, who would benefit more from labour market regulations such as minimum wages and dismissal restrictions. An increasing number of countries have laws and policies to help equalize women’s status at work. Virtually all countries have maternity leave legislation of some sort; most also prohibit maternity-linked discrimination, such as harassing or pressuring pregnant workers or young mothers to resign (ILO, 2014). Measures such as these improve women’s employment opportunities and experiences, reduce child mortality and improve mothers’ health (ILO, 2015). However, enforcement is an issue. Recent data show only 28% of employed women worldwide are effectively protected through cash maternity benefits (ILO, 2015). And for most women working in informal jobs, maternity leave legislation is meaningless.

The ILO recommends maternity protection along with public spending on work–family measures, which help advance women’s opportunities for good quality work and address stereotypes of masculinity that undervalue men’s involvement in caregiving (ILO, 2014). A comparison of Finland and Norway with Japan and the Republic of Korea showed that family-friendly policies and flexible work arrangements could enable more women and men to balance work and family lives, promote fertility and encourage continued female labour force participation (Kinoshita and Guo, 2015). Some countries, including Costa Rica, Ethiopia, Mexico and South Africa, support the work–family needs of the most vulnerable by providing public child care services (ILO, 2014).

Equal parental sharing of family responsibilities should also be supported by paternal leave. By 2013, some kind of child-related leave for men in paid work was provided in 78 of 167 countries. Payment for paternity leave, where it exists, is often low (ILO, 2014). Research from countries including Brazil, South Africa and the United Kingdom shows many men are reluctant to take paternity leave due to earnings loss or fear it could damage their careers(Levtov et al., 2015; Williams, 2013). Poor allowances for and uptake of paternity leave can be linked with persistent stereotypes of women as caregivers and men as breadwinners.

Sharing parental responsibilities can challenge the gendered division of child care, empower women economically and increase gender equality in the labour force by helping mothers enter or re-enter paid employment or complete their schooling (Ferrant et al.,2014; Morrell et al., 2012; UN Women, 2008).

Only 28% of employed women worldwide are likely to receive cash maternity benefits

Women and girls continue to do more unpaid and caregiving work

Gendered patterns of unpaid domestic and care work run deep, and seem little affected by rising levels of women’s education. A study examining increased school enrolment levels for girls in Bangladesh and Malawi found no impact on the imbalance of girls’ and boys’ domestic work (Chisamya et al., 2012).

Some see this imbalance as a root cause of women’s inequality and unequal access to education, employment and public services (Razavi, 2016). Women in many countries, including Italy, Japan, Mexico and Pakistan, do at least twice as much unpaid work as men (Figure 16), and work longer hours than men in almost all countries if paid and unpaid work is combined (UN Women, 2015c).

Women in many countries do at least twice as much unpaid work than men

Girls and women disproportionately bear the burden of household chores, including time-consuming tasks such as collecting water and firewood, even while in school. This affects girls’ attendance and educational attainment, thus reducing equality in outcomes. In Ghana, research using four rounds of the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) (1993/94 to 2008) found that halving water-fetching time increased school attendance by an average of 2.4 percentage points among girls aged 5 to 15, with a stronger impact in rural areas (Nauges and Strand, 2013).

Some small-scale interventions have shown limited success in improving gender-sensitive attitudes and women’s unpaid work balance. An adult literacy programme in rural Nepal increased recognition by family and community of women’s unpaid work by engaging marginalized women and some men in collecting data on women’s use of time. This helped achieve more equitable distribution of women’s unpaid care work in some communities (Marphatia and Moussié, 2013).

Adolescent girls do more domestic work than boys, which can hinder their completion of secondary education. Overall, household survey data suggest between 40% to 80% of adolescents do some domestic chores (up to 28 hours a week) in the 17 low and middle countries with available data; the share of adolescent girls involved in domestic work is uniformly higherthan boys’.

Decent work for all requires a lifelong learning perspective

Supportive policies can promote gender equality in the labour market and should be part of an integrated approach that enables gender equality in and through formal schooling and delivers lifelong learning opportunities for all.

Formal, non-formal and informal education throughout life can contribute to substantive gender equality by providing all women, girls, boys and men with timely, responsive and relevant learning opportunities. Good quality lifelong learning opportunities are especially important for girls and women and those who have been marginalized from formal schooling, who make up the global majority of those out of school and/or lacking basic literacy.

Gender gaps in basic proficiencies, such as numeracy, are much worse for older women. In OECD countries, gender gaps in numeracy are narrower among 16- to 24-year olds than among older cohorts, even after adjusting for educational attainment. In Italy, the adjusted gender gap for women aged 46 to 65 is 11 points; among women aged 16 to 24, the gap vanishes (Figure 17).

Lifelong learning opportunities can fill the gaps of inadequate formal schooling through literacy and numeracy acquisition. Vocational training can provide skills for work, facilitate access to wage employment, improve women’s status in work, and equalize pay and working conditions, e.g. by enabling women to obtain professional qualifications outside the formal education system. Lifelong learning can enhance women’s financial autonomy, confidence and self-reliance, as well as their participation in other spheres of life (UNESCO, 2006).

Algeria’s Literacy, Training and Employment for Women (AFIF) programme enables women to obtain professional qualifications in trades such as computing, sewing and hairdressing. It has trained and empowered more than 23,000 women aged 18 to 25, helping them with workplace integration or enabling them to generate their own income with government support (UNESCO, 2016c).

Bangladesh’s TVET Reform Project, launched in 2006, provided training for women in skills for traditional and non-traditional work, including motorcycle servicing. It included a strategy for women with disabilities, with improved physical access to training institutions, which increased their self-confidence, employment and economic status. The reforms included the 2012 launch of the Bangladesh National Strategy for the Promotion of Gender Equality in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET), which aimed to dismantle gender stereotypes and establish a supportive, gender responsive environment (European Commission,2014; ILO, 2013).